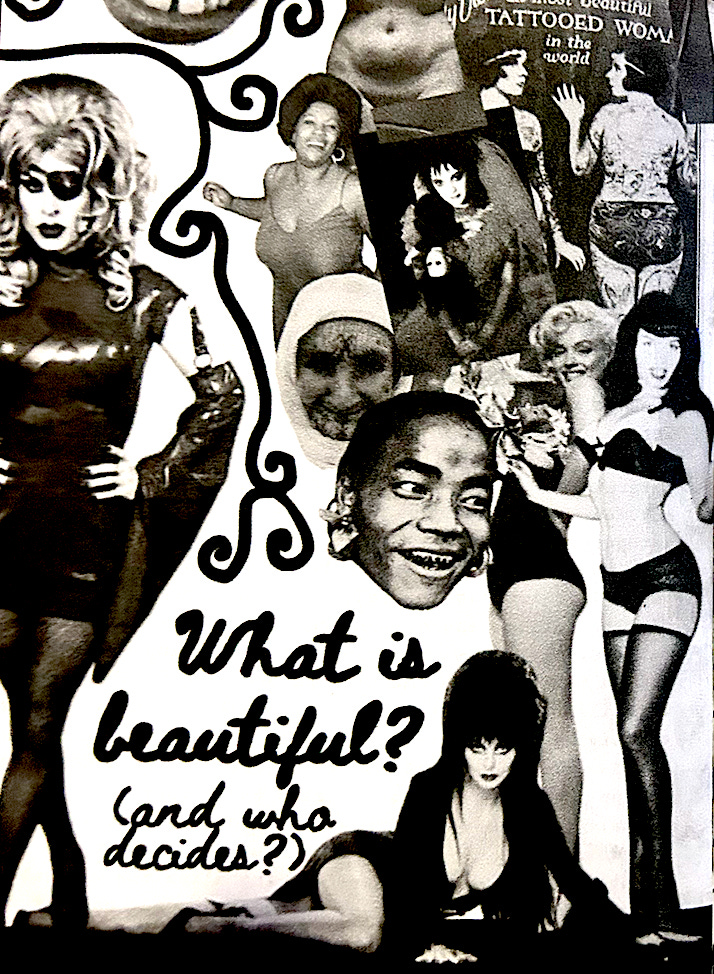

What Is Beautiful (and Who Decides)? Sex, Gender, and the Bodily Aesthetics of Morality

On how colonial aesthetics, cisnormative legibility, and capitalist desires shape the moral value of queer and trans bodies.

Within our political reality at present, which has seen a Reagenesque intensification of violence, both real and rhetorical, against gender non-conformation, it is crucial to question the instrument of beauty as a measurement of moral worth—to ask what is beautiful, and who decides?

“The beautiful is the symbol of the morally good.”

Immanuel Kant, Critique of the Power of Judgment

There is an exceptional cruelty in the judgment of the appearances of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals, as their value in society and the respect they are given has strict aesthetic criteria—and this politicized aesthetic judgment is unquestionably built upon a framework of whiteness, ablebodiedness, heteronormativity, and, in the case of femininity, the potential to be sexualized. Western ideals, which have been largely imposed at a global level as the result of the exportation of colonial values in combination with Western dominance in global capitalist markets are also largely imperialist in nature: take third genders, which have existed in countless pre-colonial societies, whose visibility in gender studies at higher education levels are frequently mocked by right-wing figures, and whose suppression, oppression, and violent repression by colonial powers (influenced by religious interpretations of divine order and natural law, themselves heavily aestheticized ideals) are disregarded. The entanglement of appearance and moral worth, in which that which is deemed beautiful by its reassurance to the normative eye assumes a role of goodness, whereas that which is deemed ugly by its subversion of hegemonic standards assumes the pathologized role of deviance or danger, is instrumental to Western colonial aesthetics and capitalist social reproduction—systems under which beauty is neither neutral nor passive, but a disciplinary technology, policing the body and naturalizing artificial hierarchies. The violence that results from the enactment of these systems is not incidental, but structural; the gaze that deems the ugly woman, the queer man, or the non-binary person hideous, monstrous, or deformed, has also marked Afro-textured hair as unprofessional, the hijab a symbol of barbarity, and drag a manifestation of predatory homosexual perversion.

Western thought has long interwoven beauty and virtue: in Kant’s Critique of Judgment, the imposition of beauty onto a subject is dependent upon the pleasure which that subject provides the judge, and the regard of a subject as beautiful, a judgment Kant describes as “subjective universal,” supposes that the judge “attribute(s) this satisfaction necessarily to every one” as he who “puts a thing on a pedestal and calls it beautiful” incidentally “demands the same delight from others,” judging “not merely for himself, but for all men.” Beauty is additionally tethered with purpose and immaculate design, themselves concepts that adorn moral value (whereby objects ill-suited for their perceived purpose definitionally cannot be beautiful). Kant’s work is also deeply androcentric, as its universal subject is typically the white European male—and therefore not a universal judge. As Sylvia Wynter argues, this mislabeled objective figure of ‘Man’ becomes the referent for humanity itself, where anything outside that configuration is rendered non or sub-human. The roots of this aesthetic-moral androcentrism stretch back to antiquity: in Aristotelian biology, the female is regarded as “a deformed male.” The male body, rational and bounded, becomes the telos of human form, while the female is marked by lack, porousness, and excess. From this foundational ontology, a long tradition emerges in which masculinity is form, reason, and order; femininity is formlessness, emotion, and disorder. The normative aesthetic begins here: in the enshrining of one body as standard, and others as degradations or deformations. The musings of male philosophers, although in conflict with the realities of the natural world, become an intellectual position othering the body that is different or unknown to them in a manner that marks such subversion as less beautiful and valuable. Aesthetic judgment thus functions as an form of biopolitical sorting, deciding who deserves not only respect but political rights, excluding those who do not conform to norms of bodily appearance, whether established by men, colonizers, or capitalists (and often, all three).

Gender-subversive or non-conforming people—especially those who are racialized, disabled, fat, or otherwise disruptive to current Eurocentric beauty norms—are rendered either invisible or hyper-visible in grotesque terms. Political philosopher, pan-Africanist and revolutionary Marxist Frantz Fanon expands upon this idea in the context of racial difference in his work Black Skin, White Masks by positing that black people living in a white society develop an unconscious and unnatural psychological response which associates blackness with “wrongness,” and that this leads to the Black individual performing “whiteness” in order to be perceived as agreeable, valuable, or beautiful, as the prescription of these values is dependent upon one’s proximity to whiteness as a foundational component of the beauty ideal. Fanon’s insights extend poignantly to gendered expectations and the gender non-conforming experience: indeed, Black women’s aesthetic otherness is manufactured by, in addition to a unique colonial hypersexualization, a degradatory masculinization, which makes the performance of aesthetic worth through proxy to a white femininity that much more difficult to accomplish. The Black woman who does not properly express the Eurocentric concept of femininity sees the consequent devaluation of her gendered role in society.

The transgender person who fails to ‘pass’ is not merely different and deformed, but deceptive (a characterization that influences much of the predatory conception of drag). Likewise, the mixed-race person, especially in apartheid-states such as the United States or South Africa, has historically been marked with the same value of deception, and regarded therefore as sinister, calculated, and predatory. With gender-subversion, as with the colonized Black body, aesthetic obscurity becomes an ontological threat—an understanding that sheds light on the conservative hyperfixation on and revulsion at transgender and gender-nonconforming visibility. The underlying aesthetic grounds for this disgust are illuminated in how these attitudes are expressed: when right-wing figures or individuals online attack transgender and queer people, like when they attack women whom they deem unattractive, they do not only reference their ideas, but their physical appearance. To the conservative, the physical expression of gender non-conformation is unnatural and thus registers as not only a disruption but a threat to established order. Gender performativity, as explained by Judith Butler, considers that what we call gender, and what some register as an immutable group of biologically founded characteristics, is actually a performance under regulatory norms. Those who fail to perform normative gender expressions convincingly are both theatrical and morally suspect. Take the actions performed by women to be deemed feminine that in fact deviate them from their natural form: shaving body hair, applying makeup, wearing push-up bras and shapewear leggings. Yet, it is not just those on the far-right of the political spectrum nor those self-identified as heterosexual who employ this tactic: within both progressive and queer circles, those who do not fit hegemonic standards of beauty are excluded from mainstream narratives, and even those liberals as well as leftists who champion inclusivity and anti-fascism use the same tropes to mock right-wing individuals deemed ugly by the deeply racialized, sexualized, and colonialist systems they apparently seek to dismantle.

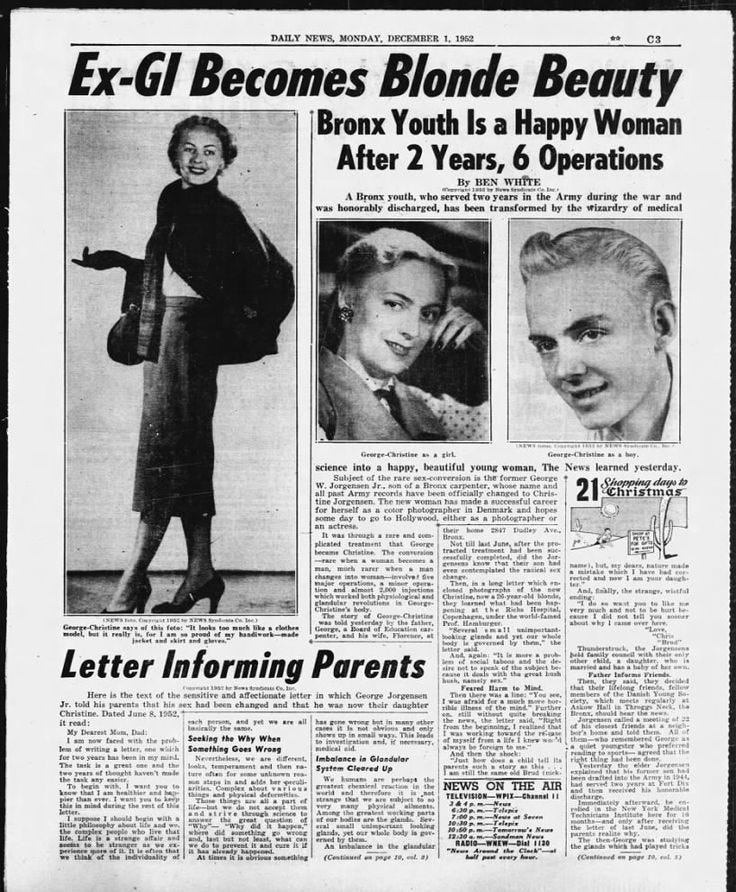

Take Blaire White: a transgender conservative American political commentator. While villified as deceptive the same way any other transgender woman is, she is also often paraded by right-wing groups as a ‘good’ transgender person, on account of her conformism to the gender binary and her depreciation of transgender and queer people who do fail to do so. White’s aesthetic flattering of patriarchal norms, and her subsequent relative acceptance in conservative circles, stands in stark contrast to the profound lack of dignity afforded to visibly transgender or nonconforming people, including by Blair White herself. In the same vein, Christine Jorgensen, American actress and singer, was widely applauded for her public transition and the fantastic work of the Norwegian doctors who performed her sex change operations in the early 1950s. Her public acceptance and even applause is often invoked to demonstrate (rightfully so) how backwards America has since progressed. Yet, the positive reception of Jorgensen, a G.I. in WWII before her transition and the takeoff of her acting career, is itself an illustration of the aesthetic criteria for the awardal of dignity and respect: other transgender women in mainstream media during the 50s and 60s, like Delisa Newton, Charlotte Frances McLeod, and Marta Olmos Ramiro, were sensationalized to lesser extents, and the news articles written of them generally had negative implications or attitudes. Jorgensen’s appearance, as a white, blonde, blue-eyed conventionally attractive woman presented a curated femininity that appeased heteronormative standards, as opposed to the white but less Aryan Charlotte Frances McLeod, the African-American Delisa Newton, and the Mexican-American Marta Olmos Ramiro.

Queer expression, too, is subject to aesthetic discipline: RuPaul’s Drag Race, the reality competition show that has been credited for bringing drag to the mainstream, is a fertile ground for the othering of those who do not adequately reproduce hegemonic (and heteronormative) gender aesthetics—despite the nature of drag as a metaphorical home for people that have been historically othered by society for their desire to partake in expression typically reserved for the opposite sex. For instance, at various points in the show, queens who do not pad their hips or breasts have been penalized in terms of their reception from judges. As a consequence of this system’s iteration in the show (the natural result of the competition’s existence within a society that praises gender conformation), most winners have been those who fit more neatly into a heteronormative gender binary. Drag queens who are ‘too queer,’ like transgender people who do not ‘pass,’ occupy the role of the “uncomfortable body,” which has the power to discomfort others simply by visibly existing. The types of bodies that have occupied this role have shifted greatly over time and vary widely within different cultural contexts—RuPaul herself, whose expression is considered manicured and palatable among queer circles today, has and is still treated as uncomfortable in its own right. While drag does depend upon a gender binary for its effective consumption, the punishment of performers who do not strictly adhere to that binary reinforces the same system that has suppressed queer gender expressions for hundreds of years—reiterating the broader logic that only the assimilable queer subject—the beautiful, palatable, and marketable one, which does not stir unease or provoke disgust—deserves recognition.

The tension arising from the aesthetic dissonance of the “uncomfortable body”—and the body’s politicization—is further intensified within what Spanish writer Paul Preciado calls “pharmacopornographic capitalism” wherein makeup, cosmetic procedures, and hormone therapies obscure the boundary between natural and manufactured identity, and the heteronormative hegemony that is the gender-binary becomes a necessary tool of control: “the pharmacopornographic industry is striving for the exponential control and production of your desiring body” to produce “a living political prosthesis: a body that is compliant enough to put its potentia gaudendi (…) at the service of the production of capital.”

“Preciado pairs his description of bodily transformations with theoretical and historical analyses of the capitalist technologies that not only produce gender and sexuality, but impose these reductions onto all bodies. Thus, Preciado’s project is not only a continuation of Foucault’s writings on the hegemonic control over the body of a population, but also an extension of Judith Butler’s treatment of a performatively created gender. Preciado refuses passivity in the face of his gendered and sexual construction, so he takes up performative acts to reconstitute his identity in a way that is not legible by the pharmacoporno-capitalism that he identifies (…) While Butler discusses the performative form of gender in terms of normalized social codes, Preciado reveals the performative effect of technological and capitalist factors in the construction of a subjectivity.” Daniel Halpern, Opening Political Bodies: Gender Performativity as Resistance Under Pharmacopornographic Capitalism

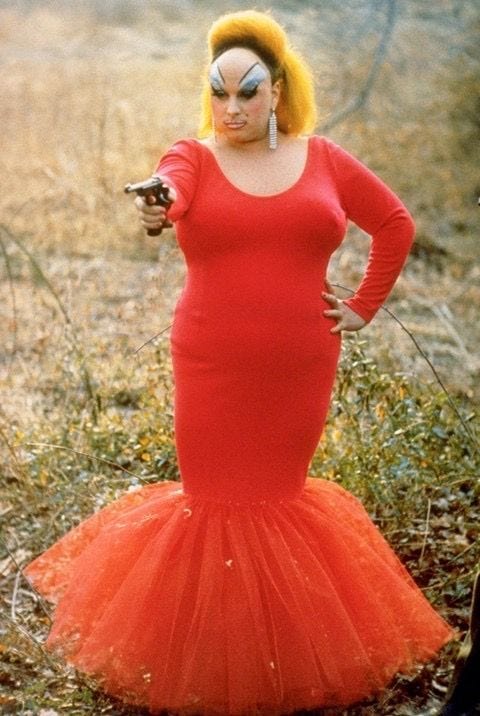

Queer performance art has been known to make an effort to invoke the discomfort and disgust associated with the uncomfortable body deliberately to challenge the viewer’s preconceptions—one notable example being Divine, named “drag queen of the 20th century.” Unlike more sanitized and broadly appealing drag performances, Divine, self-described as “filthy,” embraced the disgust and moral devaluation associated with challenging conventional aesthetics. John Waters, the filmmaker associated with Divine’s rise to fame, said Divine “didn't want to pass as a woman; he wanted to pass as a monster.” Like Divine, many artists choose not to shy away from the moral outrage that results of their non-conformation to gendered societal norms. Intersex artist Vaginal Davis blends punk, drag, and grotesque caricature to challenge audience’s beliefs about gender, sexuality, and race. Within the symbolic order of a heteronormative capitalist society which depends upon submission and compliance with existing power structures, gender non-conforming people are rendered ‘abject’, as Julia Kristeva put it, to the social order, thus provoking disgust, where disgust is political: as Sianne Ngai explored, aesthetic categories reflect social anxieties about labor, class, and sexuality—anxieties which deepen when their subject rejects commodification. This can be observed in the converse acceptance of characters like Robin William’s ‘Mrs. Doubtfire’ and Eddie Murphy’s ‘Big Momma,’ whose heterosexualized depictions provide comedic relief and, rather than challenging established gender norms, reinforce them in exploitative performances employing wigs, lipstick, and fake breasts, not as an exploration of gender expression, but as a reiteration of heteronormative tropes to incite laughter at the man in the dress. The performance which takes no political risk is not met with the same revulsion because it stirs no anxiety.

The disgust that results from genderqueer non-assimilation also removes dignity and respectability from its subject: drag queens and gay men in general become predators and corruptors. Like Anita Bryant’s “Save Our Children” campaign against gay marriage and visibility, today’s outrage at drag queens reading to children is evidence of the morality that we attribute to the object which is aesthetically pleasing over that which is displeasurable. The obsession in Western conservative politics with transgenderism, where even cisgender individuals become suspect and are consequently ‘transvestigated,’ and the increasing popularity of the ‘TERF’ movement (trans-exclusionary radical feminism) reveals the implications of deep-seated aesthetic aversion: transgender and queer people become suspected of crime and depravity for their existence as different and uncomfortable bodies, and their visibility in public becomes a cause for deep social concern, where children are the victims of an insidious agenda that seeks to corrupt their innocence and groom them into homosexuality. The ugliness with which gender-nonconforming people, as well as non-queer men and women who simply do not perform their gender adequately by means of existing in their natural state, is reproduced constantly in film and media: in The Wizard of Oz, where the ‘good witch’ is blonde, blue eyed, white, wears pink, and speaks softly, the ‘wicked witch’ has black hair, brown eyes, wears ill-fitting black garments, speaks harshly and loudly, and—perhaps most strikingly—is anything but white. During their first interaction, Dorothy remarks on the good witch’s beauty, as if beauty (and a heavily racialized concept of it) is symbolically good all on its own—and it is.

The counterculture movements that evolve in opposition to the racialized, gendered, ableist, and sexualized aesthetic hegemony in which humanity currently resides suggest an alternative: a logic that questions what is beautiful and what beauty should mean. Jamaican philosopher Sylvia Wynter advocates for the de-centering of the “colonial figure of Man” and a reimagination of the person beyond Eurocentrism. Paul Preciado calls for widespread “gender-hacking,” refusing existing cisheteronormative conceptions of beauty and worth. Even celebrated queer artist Frida Kahlo embraced the subversion of gendered fashion norms, as well as bodily differences and facial hair in her self-portraits. Philosophers and artists alike have long sought the dismantlement of the regime of beauty itself. The aesthetic regime that moralizes appearance creates and perpetuates violence by marking its victims as ugly, abnormal, disgusting, and insidious. To resist this regime, each person must work to abolish the colonial gaze that pervades their aesthetic and thus moral judgment in order to neutralize subversive expression which does no harm in and of itself. The person must also understand gender non-conforming artistic expression not as a romanticization or a decoration but a struggle for existence under a system that rewards only submission and marketability. So, I ask the reader to ask themselves: what is beautiful, and who decides?

Whenever i meet or see someone on tv no matter their gender or what their preferences are, I always listen more than look because it’s easy (at least it is for me) to recognize that someone is attractive and maybe has no personality versus another person that expresses themselves so clearly and makes sense. That’s the kind of person that I find intriguing and pay more attention to. I guess I’m at an age (almost 54 ) right now where in my mind beauty fades and we get older but no matter who I’m friends with or talking to or meet and no matter what their position is politically or personally, I try to see the good in each person that I meet rather than immediately judging them. I know what it feels like to be looked at and literally told by doctors and specialists that I look fine so what could be wrong with me? and I’ve been sick for four years now and I’ve had people meet me and think because I have blonde hair that I’m dumb as dirt and I sort of pretty much laugh at that because I love to be underestimated. Your thoughts and beliefs and facts matter and I enjoyed reading your comments- it was definitely an article that makes one stop and think before answering quickly -thanks so much for sharing⭐️