White Zombie: Vodou, Haiti, and the Colonial Aesthetics of Fear

In the 18th century, Vodou inspired a revolution. Now, it is the non-substance of cheap thrills in horror films.

Vodou has instilled fear in European and Christian minds alike since being first observed by colonizers. It is a source of fascination, fear, and, most significantly, vilification. The Haitian religion and its American cousin have been condemned, banned, smeared, maligned, and tokenized in film, music, and art, where traditional symbols associated with its practice are used to inspire some sense of divine fear in Western audiences through heavily racialized narratives that characterize Vodou as a type of chaotic devil-worship which kills everyone in its path. It goes without saying that the reality is much different: both Vodou and Voodoo are rich spiritual traditions rooted in West African belief systems which emphasize healing, community, ancestral reverence, and harmony with the spiritual world, each shaped by their unique but heavily intertwined histories with the slave trade. Exactly why Vodou strikes such a deep chord of terror in the Western mind is inseparably connected to systems of racism and colonialism, and informed by the colonial fear of revolution.

For hundreds of years, Haiti—then known as Saint-Domingue—was a brutally occupied French colony—one of the wealthiest colonies in the world— whose infrastucture was built on the backs of enslaved Africans. The island nation’s history was plagued by extreme violence at the hands of the French, whose racial class system saw only a handful of elites controlling the country. In 1791, this would all change. On the 14th of August, thousands of enslaved people attended a gathering in the forest of Bois Caïman in Saint-Domingue, where they invoked the Iwa—spirits—in a Vodou ceremony that would kickstart what would become known as the Haitian revolution. Two of the slave leaders who gave the directive were vodou high priest Dutty Boukman, and Cecile Fatiman, another legendary spiritual leader. What would follow was a bout of retribution beyond France’s worst nightmares, and, after years of war, Haiti’s independence. It is no wonder that the religion which dominated the slave colony—and was central to their fight for independence—would then be vilified relentlessly by Western powers who had gained so much from the exploitation of millions of Africans, and who lost so much when said Africans chose to fight back in a historic revolt that would become the largest slave uprising since that of Spartacus during the Roman Empire, etsablishing the first independent black country in the Americas.

Vodou’s succesful weaponization during those fateful 12 years as a means by which to empower a people to take back their freedom saw the religion deemed as an affront to European colonial authorities and institutions, threatening the supremity of white colonialists’ political and cultural control over much of the world at the time. The next centuries would see Vodou’s distortion by the colonial gaze for the colonial mission—a perversion that persists today, as we were so kindly reminded during the U.S. presidential elections of 2024. Vodou was quickly vilified as “primitive” in a desperate effort to paint Africans as primitive and fundamentally incompetent to develop and their own functional systems, both spiritual and political. The latter, already disproved by Haiti’s overthrow of French tyrrany. Now, they were grasping at straws, and they would use every tool within their power to slant and defame Vodou’s influence and legitimacy, using its imagery as a symbol of everything the colonizers feared. This is the genesis of the violent associations that have plagued Vodou ever since and tokenized it as a staple of the horror genre.

Voodoo, as far as whites were concerned, was not a religion, but an exhibition of savagery, fetish and demon worship, animal sacrifice, cannibalism, nudity, drumming, sexual promiscuity, and interracial orgies. Among enslaved men and women in New Orleans, however, it represented what a true liberation force could look like. Those already suspicious about what enslaved people were doing religiously were now terrified at the prospect that their “Voodoo” would inspire domestic rebellions.

Christopher L. Newman, “Savages and Sable Subjects”: White Fear, Racism, and the Demonization of New Orleans Voodoo in the Nineteenth Century

Vodou’s perceived impalatableness by the West (and many religious states in the global south) today is thus the lasting effect of a centuries-long smear campaign that saw missionaries employed to spread lurid tales of “black magic” (itself a heavily racialized term) and sensationalize sagas of human sacrifice, possession, and zombification, and its subsequent absorption into film and theater as the image of terror, chaos, and devil-worship. One of the most consequential storytellers of this breed was William Seabrook, an American ‘explorer’ best known for his 1929 book The Magic Island. As George Currie, a reviewer for The Brooklyn Daily Eagle noted that the collection of hearsay, legend, and speculation, which was named a best-selling non-fiction books at its time of publication,"reeks with sacrificial blood, the odor of cadavers, the sinister breath of witchcraft, the horrendous exaltation of unholy terrors slaked in the steaming passions of human animals. It is a grim story of Voodooism, this The Magic Island, filled with sickening mummeries, repulsive rituals, orgiastic expiations and propitiations.” Seabrook’s sensationalized account of Vodou (and the zombie, itself a figure from Haitian folklore) was taken as historical fact, and the public had never before been so mordbidly intrigued and radically appalled by a religion they knew so little about.

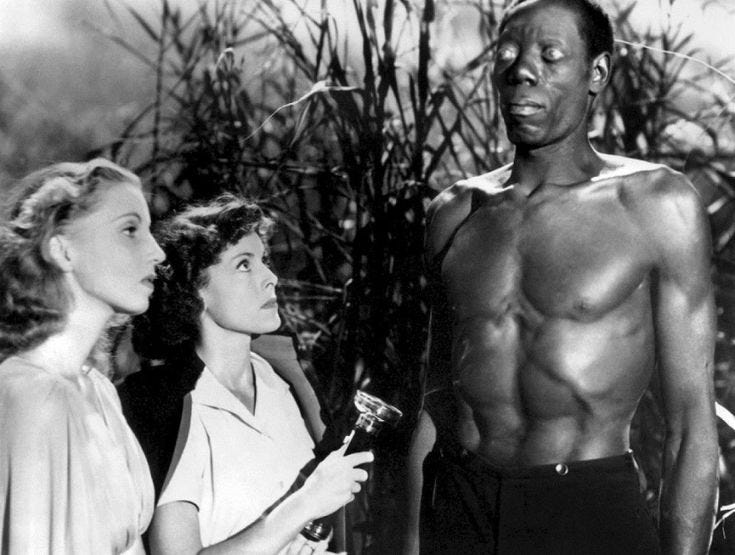

The Magic Island was the basis for the then-on consistent employment in film and literature of Haitian Vodou and the zombie as quintessential villains in horror narratives, most notably with the cult classic White Zombie (1932), where Bela Lugosi plays Murder Legendre, a ‘zombie master’ of ambiguous ethnicity, illustrated as an outsider from both the zombified slaves and the white middle class, who uses Vodou to seduce Madeleine Short (Madge Bellamy), an engaged white woman. Already glaring is the association between slavery and zombification—with zombies as mindless but obedient, whose only virtue is the work they can do for plantation owners such as Robert W. Frazer’s character Charles Beaumont. The zombie trope in Western media has sustained itself but has also become regrettably removed from its roots in a time and place when Black Haitians were the targets of a persistent deliberate effort to delegitimize and belittle their autonomy, capability, and independence. The zombie is a corpse reanimated by a master, to whom the zombie becomes subservient, and their nature as undead comes with an apathy for both their existence and their complete lack of autonomy.

Madeleine’s character is the embodiment of purity: an innocent, beautiful, engaged, white woman who is being preyed upon by Legendre, who uses black magic (literally speaking) to seduce and zombify her. The sacred religion becomes a racial symbol for corruption, sin, and human inhibition. Upon learning of her fate, her fiance laments “Not alive…in the hands of natives…better dead than that!” It is no coincidence that the zombie theme is also tied to sexual corruption and depravity; a consequence of the imposition of a white puritan worldview onto a foreign people’s sexuality uninhibited by religious shame. The objectification of the white woman as unable to resist the sexual temptations forced upon her by the savage other is a reflection of deep-seated colonial anxieties—projecting forbidden desires onto the racialized body while framing the white woman as both victim and symbol of cultural purity under threat. The zombie is the figurative offspring of an interracial reproduction, reinforced by the ambiguous and interracial undertones of Legendre’s character, who presents as a white man but employs black magic for his bidding, and who fits into neither group.

George Marshall’s 1940 classic The Ghost Breakers features a white woman played by Mary Carter who inherits a plantation in Cuba only to find it festering with ghosts and zombies, who cause a grave inconvenience to her ambitions:

The Black men here are either buffoons or catatonic, but all these films in one way or another harbor the same great fear—less crudely expressed—about proximity to Blackness, always threatening to penetrate white society. Now the zombie may richly signal any number of social failings (war, plague, the bureaucratic approach to the “disposable” masses), but the figure cannot escape its racialized birth. Somehow the migration away from these original anxieties announce a still lingering, merely unnamed haunting, a past too unspeakable to ever confront.

Kelli Weston, Grave Legacies: The Racialized Origins of the Zombie Myth

Films like White Zombie and The Ghost Breakers, like many others after them, capitalized on profoundly racist sensationalism, using Vodou and its symbols such as the Zombie to perpetuate fears about Blackness. The villains are twofold; the white or ambiguously colored man who uses black magic as his means to an end, representing both the anxieties around interracial relationships and general integration, and the Black characters dehumanized as zombies or rage-driven Vodou priests (take Ouanga (1936), in which Clelie, a biracial voodoo priestess, zombifies 13 men to kill her (white) ex-lover’s new (white) fiancee, a manifestation of colonial-era racism that saw Black people as not only mindless but dangerous and uncontrollable, embodying Western fears about uprisings—about enslaved people refusing their chains, about the Haitian fight for independence, and the karmic retribution served to white slaveowners.

Vodou, its American cousin Voodoo, and the horror genre have since become so deeply intertwined in Western popular culture that every other supernatural horror flick sees Vodou rituals, zombies, and most famously voodoo dolls exploited as devices which reduce Vodou to a dark, foreign, uncontrollable and immoral force. Movies like The Skeleton Key (2005) and The Haunted Mansion (2003) can be seen weaponizing Vodou in this way, tokenizing Black spirituality and transforming it into nightmare fuel. These recurring motifs depend upon the preconception of Vodou, and in many instances, Blackness as a whole, as inseperably shrouded in chaos, violence, and inexorable rage. The zombie trope, one of the longest enduring in horror media, is an unmistakeable example of Vodou’s vilification, with the zombie as a racialized figure, unthinking, and subservient, an enslaved subject who acts as a relic of another era, and the zombie-maker as a symbol of the corruption that is integration.

In the face of ongoing distortion, Vodou’s artistic expression has not remained stagnant—to the contrary, it has invariably evolved to both resist complete commodification and to reassert its sacrity and power. Take priest and painter Andre Pierre (1914-2005), whose depictions of Vodou spirits and Gods surround figures of the libeled religion with animals, adorn them with halos, and encapsulate them in saturated light, contesting Western understandings of Vodou as devil-worship or mindless chaos. Another key figure in Vodou-inspired art is Myrlande Constant, who received worldwide acclaim with her piece ‘Haiti madi 12 januye 2010’ depicting the earthquake that plagued the nation in 2010. Her embroidered Vodou flags have revolutionized not only the practice of drapo-making, but also Western understandings of Vodou and Haitian society at large. Still, in many ways, Vodou’s appropriation and exploitation as a dark, chaotic, otherly force continues to be propagated in media. In the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake that devastated so many, much of Western news coverage focused on Vodou, which many Haitians turned to for solace, instead sensationalizing their rituals, labeling them strange, controversial, even primitive—perpetuating a historical pattern wherein Vodou and other Black spiritual systems and religions are pathologized and villified when publicly practiced.

The Western conception of Vodou as chaotic and uncontrollable stems from its attitudes toward Haiti in general, and thus these beliefs reflect eachother: when U.S. politicians call Haiti a “shithole country,” when Haitian immigrants are accused of stealing and killing or consuming family pets in American suburbs, when these accusations are utilized as fodder for a presidential election, these narratives are not unilateral—instead, they represent the longstanding legacy of slavery, colonialism, and revolution, and how historical atrocities and colonial fears have allowed the painting of an entire nation as religiously primitive and politically incapable. Yet, Vodou refuses to be confined in the boundaries created for it by colonial powers. Much like its spiritual practice, Vodou's art insists on transition, growth, and revolution, constantly evolving in response to the very forces attempting to suppress or discredit it. In a world where resistance tends to be co-opted, corrupted, and sanitized, Vodou remains unapolagetically loud and complex. The persistent commodification and tokenization of Vodou and its symbols into political talking points or media tropes is a reminder that revolution is never linear—it is messy, and contested—but in the case of Vodou, it is also divine.

i just read a book chapter on this! here is a quote i think rly stood out to me from it. “Zombification conjures up the Haitian experience of slavery, of the disassociation of man from his will, his reduction to a beast of burden at the will of a master [...] the man whose mind and soul have been stolen and who has been left only the ability to work.”

there is an episode of x files where it is revealed that an immigrations officer is performing zombification rites on soldiers to abuse haitian refugees. i was interested in this particular episode and used it in a project for a class, examining how diasporic practices like vodou can be abused in the hands of white oppressors and used against the very people whose cultures, identities, and communities rely upon these practices. for a show that came out in the mid 90s it did a pretty decent job of unpacking the complexity vodou in the American consciousness. your essay does an excellent job of exploring these ideas as well!!